On December 22, I celebrated 7 years of MCAS diagnosis. Yes, I say celebrated, because getting a diagnosis in 2015 was almost unheard of and without it, I wouldn’t have been able to advocate for myself and get treatment.

This is how I describe the past 7 years:

- 2016: Total destruction and despair

- 2017: Renovating my life

- 2018: Building a support system

- 2019: Survival and self-advocacy

- 2020: Dreaming again

- 2021: Adventure and feeling

- 2022: Finding my balance

Please note: the majority of MCAS journeys are not this extreme. Many people with MCAS are undiagnosed because their symptoms are not severe.

Remission has been interesting to navigate. Sometimes I catch myself subconsciously living like I am still controlled by MCAS. For example, for 5 years, I didn’t have enough vacation time to even consider taking the time off between Christmas and New Year’s; all my paid time was spent on MCAS reactions. Last week, after receiving my 9th auto response from a coworker, I seriously had to reassess my choices. I no longer need to fear going to losing my job because I want to spend two days relaxing and eating cheese.

Last year, I had an unsatiable desire for adventure–not knowing what I liked or how long my remission would last. This year, the urgency subsided (but not my gratitude!). Instead of chasing adventure, I took pleasure in building habits. Until remission, my mast cells never permitted routine.

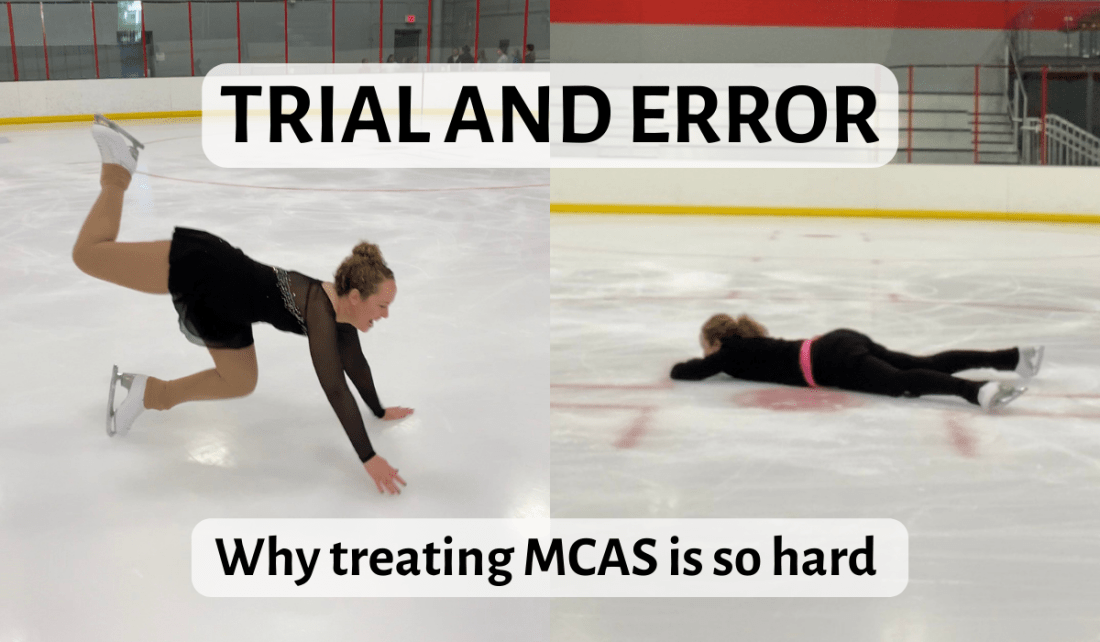

I did literally work on finding my balance: scratch, camel, and sit spins. However, the hardest work was learning how to balance adrenal insufficiency (a life-threatening complication of MCAS) and my newfound love of athletics. Although I’ve met plenty of competitive skaters with MCAS, I have yet to meet another competitive skater with adrenal insufficiency, because exercise requires cortisol. A few ruthless adrenal crises reminded me: even though my body CAN go longer, faster, or higher, it doesn’t mean I should. I need to really WANT to do the thing. And then stress dose accordingly.

Speaking of stress dosing, isolation is terrible, but this year, I re-learned that human interaction is really complicated. It’s easier to set boundaries when you’re deathly allergic to people. Other people’s expectations are especially rampant in the figure skating world. You can’t go a day without hearing “axel” and “Olympics.” Meanwhile, I’m sliding around in a pumpkin costume, most interested in “joy.”

Two weeks ago, I found myself skiing 7” of wet, heavy snow, being chased by a professional race coach yelling, “Right, left, right.” My trembling muscles warned me this would not end well, but I told myself to be grateful for this unexpected private instruction. I did not feel grateful a few days later hugging my toilet in adrenal crisis and vomiting so hard brain juice shot out my old CSF leak.

Remission or not, life is messy. I’m not making any New Year’s resolutions because I’m not pretending to be in control. Joy is my compass, gratitude is my motivator, and humor is my Band-Aid for when I inevitably get my ass kicked.

In case you missed it, on October 30, I had the pleasure of reconnecting with Dr. Afrin, my MCAS specialist from 2015-2017, in a live MCAS Q & A hosted by Mast Cell Research. Watch the recording.

And thank you to my Patreon supporters for keeping this blog going during 2022!